As new technologies arise, so does the concern of industries being replaced by these technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI) is among the most widely discussed topics. Even previously thought unreplaceable industries such as the creative arts are beginning to see AI become a disruptive presence that could endanger artists’ survival.

Many initially seemed unconcerned about AI in the arts industry. As art is the result of human creativity, AI is not widely seen as a danger to this industry.

In a Dec. 2018 Medium article by Aayush Agarwal, he writes, “Although AI can produce images that are on par or exceed the level of a human artist’s comprehension of creativity, there does not have to be any replacement of human ingenuity.“

AI can only produce based on what is available within its database, it lacks true ingenuity. However, in the same article, a study by computer scientist and professor Ahmed Elgammal at Rutger University’s Art and Artificial Intelligence Lab (AAIL) had surprising results. The peer-reviewed paper (under Experiment IV) found that the computer-generated images were rated more novel 59.47% of the time and more aesthetically appealing 60% of the time.

So as technologies develop, do previous views remain true?

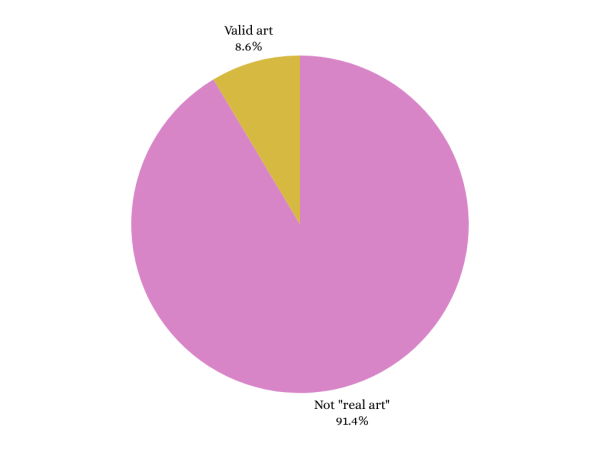

In a personally conducted survey of around 35 art students at LVA, about 91% of respondents did not define AI art as “true art.”

In this article by Medium writer and art historian Mary Rose, an “AI Artist” Emile Corsi is discussed. Rose’s closer examination brought to light the fabricated existence of a 19th-century artist named “Emile Corsi.”

In said article, Rose said, “Even the header of the blog that shared it originally, Shuttered-Gallery, admits the ‘artist never existed in reality.’ But of course, most people aren’t checking before reblogging. And they’re shocked when they are told it’s actually AI-generated.”

Observing the stylistic techniques and social media attention of Corsi, I created a survey utilizing AI-generated images to see if respondents can distinguish AI-generated artworks from real ones.

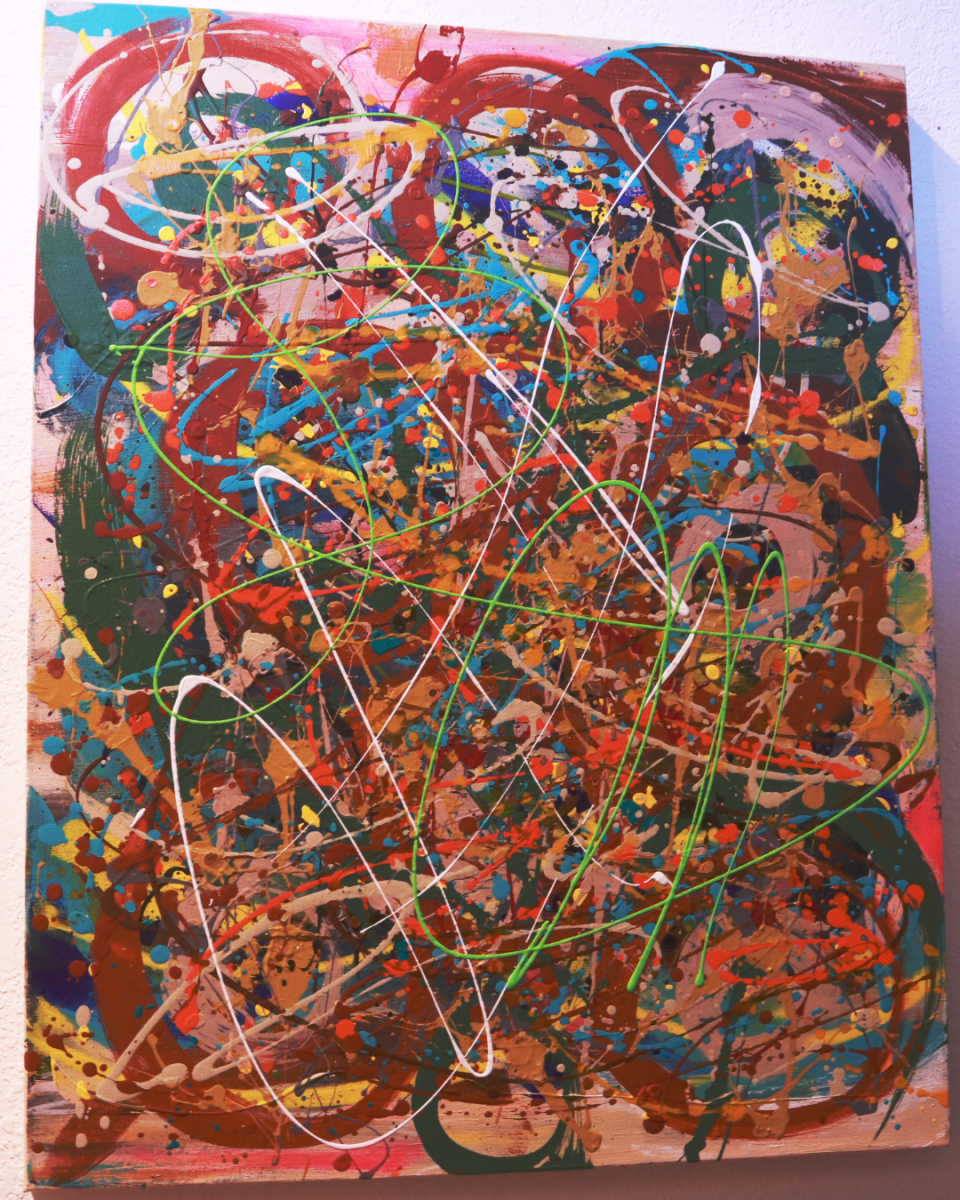

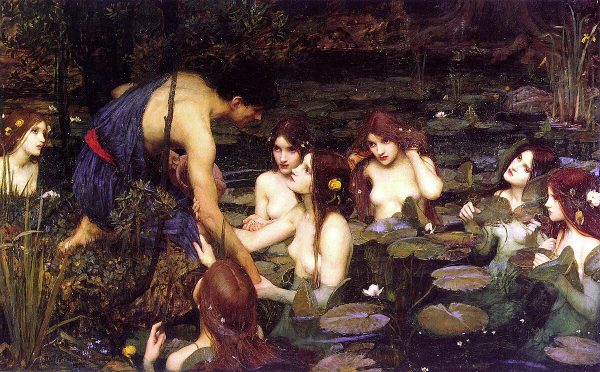

The following images generated the most drastic differences between the percentages of the first question of “whether or not AI art is ‘real art’.” (Please note that any attributions to Emile Corsi and dates are not true and may be created for a narrative.)

Respectively between the 3, responses of “real” hovered around 31.4% (11/35 respondents) to even 51.4% (18/35 respondents). Around a third to nearly half of the respondents thought these images were genuine artworks without context (such as the titles and attributions).

Analyzing the artworks, many details could easily create genuine confusion. There’s a classical style to the images, invoking the idea that these were genuinely painted with mediums such as oil paints. With subjects of classical mythology or historical man, the association with older works is further connected by viewers.

These AI-generated images bear striking resemblances to the works of Gustav Klimt (in particular Judith and the Head of Holofernes) as well as John William Waterhouse (such as Hylas and the Water Nymphs).

Older artworks by great masters such as Titian, Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Waterhouse, and so many more are entered into the public domain where their work can be entered into AI databases. As a result, AI has more immediate access, than many human artists, to artworks for its databases, training its image generation programs.

However, even contemporary and modern artists feel the impact of AI on their artwork. In many artist communities, it is well known that some AI companies will use artists’ artworks that have been posted online to various platforms to develop their models.

Illustrator Julia Bausenhardt explains on her site: “The language models and image generators need samples before they can generate anything – they can’t create text or images from nothing. The companies call this “training” – the AI is being provided huge datasets that are run through several algorithms… I’ve already found my art in the datasets of image generators like Stable Diffusion (more on that in a bit). Basically, if you can see it on the internet, it will be taken.”

Such experiences have been met with the creation of tools like “Nightshade.” Created by Professor of Computer Science Ben Zhao at the University of Chicago, Nightshade is a tool for “proactive content copyrights.”

An article from MIT Technology Review explains that Nightshade, “Exploits a security vulnerability in generative AI models, one arising from the fact that they are trained on vast amounts of data—in this case, images that have been hoovered from the internet. Nightshade messes with those images.”

As a tool, AI itself has no consciousness, but its use may present mixed perceptions.

Senior 2-D visual arts major Julie Espinoza said, “I feel like AI takes the life and the fun out of art. It’s stealing all of that creativity and generating something boring and plain with no life. Art is supposed to be shared with and communicated with, not just a plain picture with no thought or meaning behind it.”

Conversely, senior 2-D visual arts major James Childress said, “Saying AI art is not ‘real’ art is saying Marcel Deschamp’s ‘Fountain’ (1917) was not ‘real’ art either because it does not fit the standards of what majority views art is and isn’t. AI art is real and, if not already, will have an effect on our world… Artists have lost their crafts and jobs during these processes of advancement but new jobs come from them as well. Still, I believe when dealing with AI, there should be regulations and questions on where the data it gets to create imagery comes from.”

Tools have infinite potential and capabilities varying between users. Has AI’s impact yielded more benefit despite its lack of ethical nuance? Or will AI’s presence create a new standard, where artists will have to utilize programs like Nightshade to protect their content copyrights?